this week: programming-in-the-large using the module system of OCaml.

1. STRUCTURING SOFTWARE WITH MODULES

in large project: mangage high number of definitions → abstractions built on top of other abstractions.

- layers of abstractions: hide information

- divide program into components

- identifiers organised to avoid naming conflicts

module as namespace

dot-notation: access module component.

ex. List.length

or first open List then just call length

if open 2 modules having identical identifiers, the last opened module will be used.

to define a module:

module SomeModuleIdentifier = struct

(* a seq of definitions *)

end

- module name: start with an upper case

- to alias a module:

module SomeModuleIdentifier = SomeOtherModuleIdentifier

# module Stack = struct

type 'a t = 'a list

let empty = []

let push x s = x::s

let pop = function

| [] -> None

| x::xs -> Some (x,xs)

end;;

module Stack :

sig

type 'a t = 'a list

val empty : 'a list

val push : 'a -> 'a list -> 'a list

val pop : 'a list -> ('a * 'a list) option

end

# let s = Stack.empty;;

val s : 'a list = []

# let s = Stack.push 1 s;;

val s : int list = [1]

# let x,s =

match Stack.pop s with

| None -> assert false

| Some (x,s) -> (x,s);;

val x : int = 1

val s : int list = []

# let r = Stack.pop s;;

val r : (int * int list) option = None

hierachical module structure

- a module can contain other module definitions

- a signature can also contain module signatures

- if module

Bis insideA, useA.Bto get its namespace

module Forest = struct

type 'a forest = 'a list

module Tree = struct

type 'a tree =

Leaf of 'a

| Node of 'a tree forest

end

end;;

open Forest.Tree;;

let t = Leaf 42;;

2. INFORMATION HIDING

a module should come with some user manual ("contract") to indicate to clients:

- function preconditions that must be verified

- data invariants that must be preserved

- definitions that user must not rely on (cause they'll change in the future)

a module signature represents this contract, the type checker will enforce point 2 and 3.

module signatures

- a module's type is called signature or interface

- programmer can force a module to have a specific signature

to define a signature:

module type sig

(* a seq of declarations of following form:*)

val some_identifier: some_type

type some_type_identifier = some_type_definition

exception SomeException of some_type

end

to construct a module with a specific signature:

module M: sig ... end = struct ... end

to name a signature:

module type S = sig ... end

then use this name to annotate module:

module M:S = struct ... end

example: natural numbers

module Naturals: sig

(* Invariant: A value of type t is a positive integer *)

type t = int

val zero: t

val succ: t -> t

val pred: t -> t

end = struct

type t = int

let zero = 0

let succ n = if n=max_int then 0 else n+1

let pred = function

|0 -> 0

| n -> n-1

end ;;

abstract types

we can use the module normally:

open Naturals;;

let rec add: t -> t -> t =

fun x y ->

if x = zero then y else succ (add (pred x) y);;

but the invariant can be easily broken:

let i_break_the_abstraction = pred (-1);;

This don't have compiler error, as the type of pred is int, we can pass any int to it.

⇒ use abstract types that will give no choice to the client but to respect the rule.

in the signature:

module Naturals: sig

(* Invariant: A value of type t is a positive integer *)

type t (* remove the type value of t in the signature *)

val zero: t

val succ: t -> t

val pred: t -> t

end

then calling pred (-1) will cause an error.

→ we have hiddent the definition of the type t

the sig don't publish t's implementation anymore, so the checker ensures clients can't use that fact

t is called an abstract type.

With abstract type, users can't do pattern matching, to allow pattern matching while forbidding the direct application of data constructors, OCaml provides a mechanism called private types. see here.

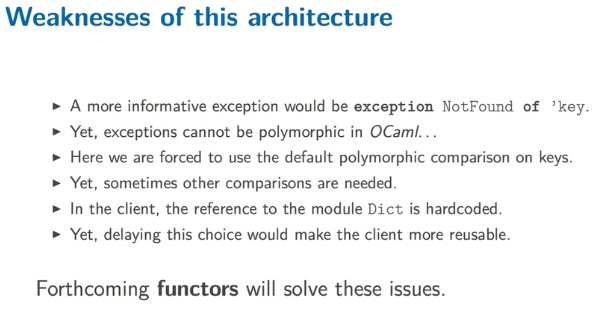

3. CASE STUDY: A MODULE FOR DICTIONARIES

An example of using abstract types to increase the modularity of programs.

Define a dictionary signature:

module type DictSig = sig

type ('key, 'value) t = ('key*'value) list (* internal repr of the dict is exposed@ *)

val empty: ('key, 'value) t

val add: ('key, 'value) t -> 'key -> 'value -> ('key, 'value) t

exception NotFound

val lookup: ('key, 'value) t -> 'key -> 'value

end;;

module Dict: DictSig = struct

type ('key, 'value) t = ('key*'value) list

(*......implementation *)

end;;

Then a client can use this module:

module ForceArchive = struct

let force = Dict.empty

let force = Dict.add force "luke" 10

let force = Dict.add force "yoda" 100

let force_of_luke = Dict.lookup force "luke"

let all_jedis = List.map fst force (* here client knows that dict is a list!*)

end;;

This is not very good if the internal implemtation of Dict is changed into

For instance, change the implemention into a BST:

type ('key, 'value) t =

| Empty

| Node of ('key, 'value) t * 'key * 'value * ('key, 'value) t

→ change the signature of module to abstract type.

4. FUNCTORS

Functors are functions from modules to modules. In other words, a functor is a module parameterized by another module.

Continue the last example, we want to choose a Dict implementation externally. → module functor

To declear a functor, add the Dict module in the parameter

module ForceArchive (Dict: DictSig) = struct

let force = Dict.empty

let force = Dict.add force "luke" 10

let force = Dict.add force "yoda" 100

let force_of_luke = Dict.lookup force "luke"

end;;

Then we can call the explicit implementation in the client:

module Dict_list: DictSig = struct

...

end;;

module Dict_bst: DictSig = struct

...

end;;

module Client1 = ForceArchieve (Dict_list)

module Client2 = ForceArchieve (Dict_bst)

- a functor is a module waiting for another module

- syntax:

module SomeModuleIdentifier (SomeModuleIdentifier: SomeSignature) = struct ... end;;

- to apply a functor to a module:

SomeModuleIdentifier (SomeModule) - signature of a functor:

functor (ModuleIdentifier: SomeSignature) -> sig ... end

example: Set and Map

They expects a module satisfying the following signature:

module type OrderedType = sig

type t

val compare: t -> t -> int

end

Once a module E has this signature,

Set.Make (E)offers over sets ofE.telementsMap.Make (E)....

type parameterization of exception can be done using functor.

In signature declaration:

module type DictSig = sig

(* before: type ('key, 'value) t *)

type key (* make the key not polymorphic *)

type 'value t

val empty: 'value t

val add : 'value t -> key -> 'value -> 'value t

exception NotFound of key (* parameterize exception type in signature *)

val lookup: 'value t -> key -> 'value

end;;

In the implementation make the module a functor: add the Key module as argument

module Dict(Key: sig

type t

val compare: t -> t -> int

end) : DictSig = struct

type key = Key.t (* key is the type of the Key module *)

...

end;;

(... don't quite get it......)

type constraint: DictSig with key=string

Part 7 of series «Introduction to Functional Programming in OCaml»:

- [OCaml MOOC] week0: intro and overview

- [OCaml MOOC] week1: BASIC TYPES, DEFINITIONS AND FUNCTIONS

- [OCaml MOOC] week2: BASIC DATA STRUCTURES

- [OCaml MOOC] week3: MORE ADVANCED DATA STRUCTURES

- [OCaml MOOC] week4: HIGHER ORDER FUNCTIONS

- [OCaml MOOC] week5: EXCEPTIONS, INPUT OUTPUT AND IMPERATIVE CONSTRUCTS

- [OCaml MOOC] week6: MODULES AND DATA ABSTRACTION

Disqus 留言